Three short ones

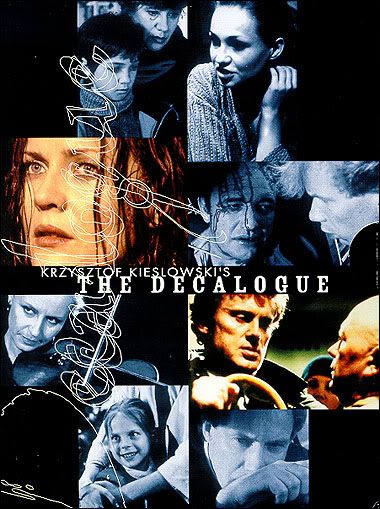

In lieu of three posts, here's a conglomeration of what I've watched lately. The Ten (David Wain, 2007) I am the queen of hyperbole; for instance, how many times can I say that a movie was one of my most anticipated of the year? Add another one to the total. The Ten is the comedy of the year, from David Wain (The State< Stella, Wet Hot American Summer, all of which I am a fanatic for) and Ken Marino. Here's a comedy that's foul, juvenile, and sacreligious, all without being too stupid. Everyone and their mom is in this movie, from Jessica Alba (cute and surprisingly funny) to Winona Ryder to Justin Theroux as Jesus. Ten vignettes, each interpreting a commandment. Wain said he wanted to make a funny version of The Decalogue, and he most definitely succeeded. Hilarity on the level of Wain's other projects abounds. 9/10  Tenebre (Dario Argento, 1982) If you ever visit the actual site, you'll probably notice the new header, a beautiful brunette sitting at a table, holding a gun with an almost indescribable expression: part fear, part laughter, part sadness. This is my favorite moment from Tenebre, Argento's incredibly beautiful giallo masterpiece. It's suspenseful (I didn't see the end coming, for sure), but more than that, it shows the beauty that is possible in horror movies. When one character falls through a mirror with her throat slit, right into the camera, it's more stunning than anything else. Not to sound like a serial killer or anything. Argento topped himself here, horror with a surprise ending that satisfies the gore enthusiast as well as the cineaste. 9/10  Martin (George A Romero, 1977) Finally, George A Romero's problematic, but rewarding, Martin, about a young man who thinks he's a vampire. Is he, or is he just insane? Well, he gets the blood from his victims with the use of a razorblade with fangs, only one of the clever details in the film. But while the details are solid, the movie as a whole is less so. Martin changes mid-film, from a scared/scary young man who never speaks more than three words at a time to a man who enters a relationship with a married woman without wanting to kill her. How? Why? Martin's character is unfufilled; I wanted to know something about his past, how he came to believe he is (or be) this creature. But the very last scene is one of the best examples of dramatic irony I've ever seen, so I recommend seeing it if only for that. 7/10 Labels: 1977, 1982, 2007, dario argento, david wain, george a romero |

Decalogue 5: Thou shalt not kill. Kieslowski's only overt political statement of the series lies in this anti-death penalty piece. Instead of giving a total picture of a murderer, we see the few hours before the crime, during which the young man is mostly silent and isolated, but tries to reach out to the outside world (throwing the food at the little girls, to their delight) with little success. The crime is done, then the film cuts to after the trial, right before the execution. There is an idealistic young lawyer who has his whole livelihood put into question through the verdict, and the young killer who just wants to be buried in his family's plot. An incredibly realistic, humane portrait of the justice system. There are no judgements on Kieslowski's parts, just facts and people.

Decalogue 5: Thou shalt not kill. Kieslowski's only overt political statement of the series lies in this anti-death penalty piece. Instead of giving a total picture of a murderer, we see the few hours before the crime, during which the young man is mostly silent and isolated, but tries to reach out to the outside world (throwing the food at the little girls, to their delight) with little success. The crime is done, then the film cuts to after the trial, right before the execution. There is an idealistic young lawyer who has his whole livelihood put into question through the verdict, and the young killer who just wants to be buried in his family's plot. An incredibly realistic, humane portrait of the justice system. There are no judgements on Kieslowski's parts, just facts and people. Decalogue 6: Thou shalt not commit adultery. Along with part 5, part 6 was made by Kieslowski into a slightly longer film for foreign distribution; I can see why, as these two are the parts with the most universal storylines. A young man spies obsessively on his neighbor and falls in love with her. When he finally gets his chance to be with her, he realizes love (or lust) isn't as ideal as he had thought. Kieslowski uses a potentially creepy situation to illuminate the fact that life is almost never what we think, which can be both a good and a bad thing. The acting in this one is the best of any of the films, provoking empathy on my part.

Decalogue 6: Thou shalt not commit adultery. Along with part 5, part 6 was made by Kieslowski into a slightly longer film for foreign distribution; I can see why, as these two are the parts with the most universal storylines. A young man spies obsessively on his neighbor and falls in love with her. When he finally gets his chance to be with her, he realizes love (or lust) isn't as ideal as he had thought. Kieslowski uses a potentially creepy situation to illuminate the fact that life is almost never what we think, which can be both a good and a bad thing. The acting in this one is the best of any of the films, provoking empathy on my part. Decalogue 8: Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor. Perusing the imdb message boards (a frequent vice of mine), I found that part 8 is generally the least favorite of those who have seen the series. I think the story is the most compelling, for certain: an ethics professor is confronted by a ghost from her past, the grown-up version of the little girl who she sent to almost certain death during the Nazi occupation. Most of the tales are surprisingly optimistic at their ends (Kieslowski sees the glass as half-full!), but none more than this one. The two women talk, and the professor gains peace of mind, as she had always wondered what happened to that little girl, and the visitor regains confidence in the good intentions of mankind. I was struck by how the moment portrayed in the film was definitely the defining moment of both characters' lives, trumping that moment forty years ago.

Decalogue 8: Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor. Perusing the imdb message boards (a frequent vice of mine), I found that part 8 is generally the least favorite of those who have seen the series. I think the story is the most compelling, for certain: an ethics professor is confronted by a ghost from her past, the grown-up version of the little girl who she sent to almost certain death during the Nazi occupation. Most of the tales are surprisingly optimistic at their ends (Kieslowski sees the glass as half-full!), but none more than this one. The two women talk, and the professor gains peace of mind, as she had always wondered what happened to that little girl, and the visitor regains confidence in the good intentions of mankind. I was struck by how the moment portrayed in the film was definitely the defining moment of both characters' lives, trumping that moment forty years ago.