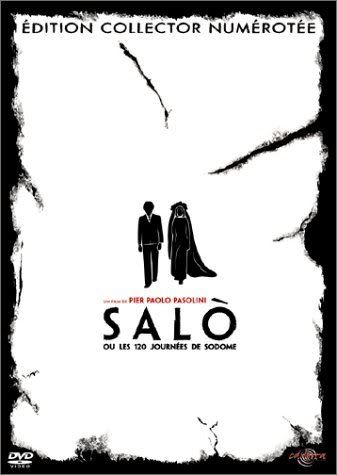

Salo (or the 120 Days of Sodom) (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975)

Note: this entry is taken almost entirely (although edited for more clarity) from my movie journal ramblings the day after watching Salo. It took me a little while to be able to get my thoughts on paper, but once I started, it was hard to stop. I finally saw Salo after years of seeking it, having heard that it's the most disturbing film of all time. This is a movie whose reputation always precedes it, but it's also a film that I can say without (much) pretension that most people who have seen it aren't smart (or educated, more likely) enough to really appreciate it. There are so many posts on IMDB (my guilty pleasure of the film world) about how it's not shocking or disturbing or whatever someone may have expected. This isn't a film for 16 year old gore freaks, as it may have been portrayed to be. A lot of people, it seems, come into this film expected Guinea Pig, and they're sorely disappointed. Instead, it's about human cruelty, life during wartime, things like that. If someone doesn't at least understand the basics of Dante's Inferno and Italisn fasciscm, they won't completely (as completely as one can, anyway) get what Pasolini was trying to say, pure and simple. Sure, many of the actions shown are shocking in and of themselves, but just to take them as that (and more, to be disappointed in the non-shocking nature of those acts in a void) is immature and ignorant. This is possibly the most misunderstood movie of all time. The one element that sticks out to me above all others to write about (although what a tough choice that was!) is Pasolini's decision to base the film solely on the persepctive of the victimizers, in direct contrast to that of the victims. The president, his libertine companions, the whore-storyteller - these are the only people that we as the audience get to know. They are in plain view, yet enigmatic; completely taboo- and secret-less, yet not completely understandable (based on their very committment to depravity and full disclosure). We only see the victims through the eyes of those in power, and I actually began to feel disgust for the victims from time to time. The only things the victims say are basically pleas - to their captors, to their god, to whomever will listen. Then, near the end of the film, they turn on one another in order to avoid punishment. We, like their captors, want to find out their secrets, and at the same time are disgusted they would stoop so low as to sell one another out to avoid their inevitable fate. But it shouldn't be surprising - the whole film, the victims are almost infuriatingly meek, unwilling at all to stand up (except one unfortunate girl, who takes her fate in time anyway), defend themselves, challenge their fates - nothing. We get angry with these children (because they are little more than that) and their weaknesses until we realize that we have fallen right into Pasolini's trap! How easy it is to hate the victim! How simple it must have been for fascism to succeed in Italy! And so on. So in his great brilliance, Pasolini puts the audience simultaneously in both groups' shoes: we are disgusted by the victims for being so weak (and reflecting in ourselves the same qualities), we see human nature (however disgusting and brutal) apparent in the captors; yet we are the same as the victims - we, without argument, swallow the scenes set before us, as disgusting as we find them. And we do swallow our fate in watching the film blindly, but it doesn't change anything, just the same as the victims' meekness changes nothing in their fate as well! That's what the victims realized, and so there we are, right back at the beginning of Pasolini's vicious cycle. An impossible movie to truly enjoy watching (or to give a number rating), Salo is yet a brilliant one, the most misunderstood, misinterpreted in film history. It is also arguably one of the most important films ever made, one that caused the murder of its genius creator. The Criterion disc states that Pasolini's goal was to impart this lesson: "Moral redemption may be nothing but a myth." That's heavy stuff, something few people willingly want to think about, but one Pasolini wanted to force us to. He is very successful, but the notoriety associated with the film does nothing but harm its intellectualism. Maybe when Criterion rereleases this film sometime this year, and it becomes readily available and not rare, will these issues be thought of popularly as a part of the movie, not just the shit-eating. Salo is a trial, one worth undertaking, but only if one is willing to accept the intellectual/spiritual challenges, not only the fortitudinal one. Labels: 1975, pier paolo pasolini |

Comments on "Salo (or the 120 Days of Sodom) (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975)"

post a comment